All fields are required

Posted in Legionella,Legionnaire's disease,Our Blog,Outbreaks & Recalls on May 15, 2019

Legionnaire’s, the disease that famously attacks not just individuals or groups but entire apartment buildings and their cooling towers, has struck once again in the United States. This time, it’s a complex of senior citizen apartments in Newark, New Jersey that’s been affected. Three people have fallen ill with the disease since it made its first appearance in the building in September. Here’s what you need to know about Legionnaires in New Jersey.

Legionnaire’s disease is a particularly deadly form of the already-formidable pneumonia. It doesn’t spread from person to person; instead, it floats through the air on aerosolized droplets of water. Often, it’s dispersed through the building via air condition or some other HVAC-related vector. That makes legionnaires unique, and particularly deadly: you don’t have to be near a sick person to get it. All you have to do is to go into a structure where it’s taken root in the cooling towers above your head.

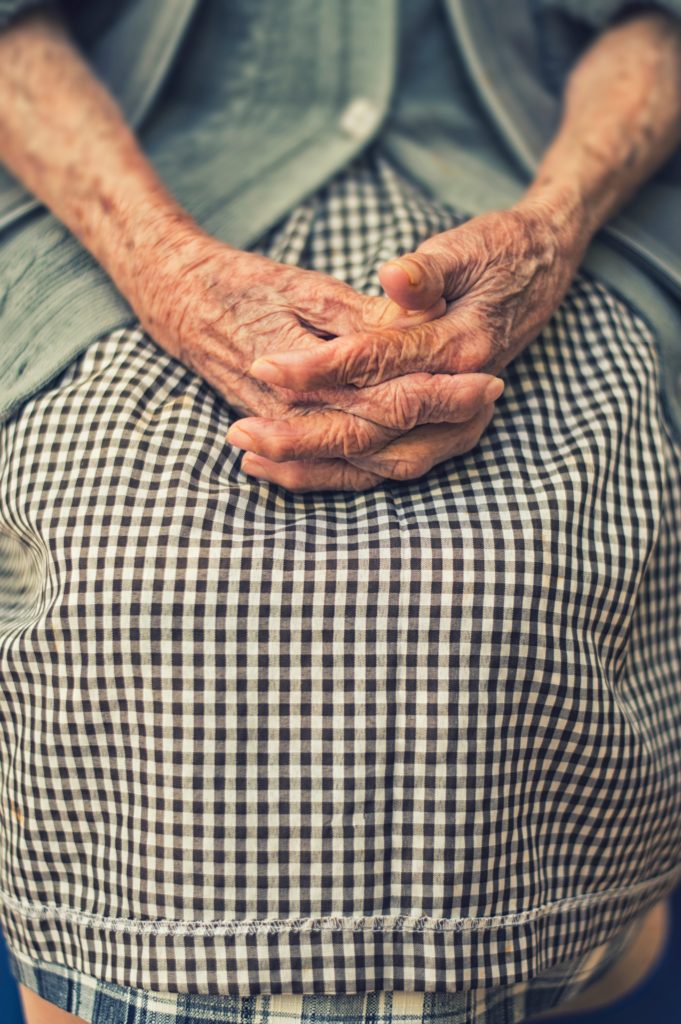

The disease usually targets the elderly, the immunocompromised, or other vulnerable populations. For an adult with an immune system firing on all cylinders, the disease might not take root in the first place, or might not do so much damage. For the very young, the very old, or those who otherwise want for more robust or complete immune defenses, legionnaires can hospitalize, disable, or kill.

Aside from those factors, there’s a few other things that can put you at heightened risk of contracting legionnaires. Mainly, it’s things that affect the functioning of the lungs, which is where the bacteria take root. If you are or have been a smoker, then you’re at higher risk of contracting the disease. Ditto for people with respiratory conditions like emphysema. Not everyone exposed to legionella bacteria develops legionnaires, but a history of lung problems makes that possibility more like.

Given that information, it makes sense that this recent Newark outbreak has affected a housing complex that’s specifically dedicated to senior citizens. They’re among those vulnerable populations — the kind of people who legionnaires successfully targets. We don’t know much so far about the condition of those three confirmed cases of illness, although as of the time of this writing it doesn’t look like anyone has died.

The bacteria don’t just spread through a building’s cooling system. They can float to a new host on water aerosolized by pretty much any source. That could be air conditioning or almost anything else that generates mist; you can get legionnaires from the mist that’s generated by your shower, or by the humidifier in your apartment. You can get it from a fountain, or from the faucet while you’re washing dishes, or from the steam that spills out from your dishwasher when you open it up.

If you’re in a building where someone’s gotten sick with legionnaires, you’ll probably be looking for ways to reduce your chance of being exposed to or contracting the disease. Like someone in a gimmicky horror movie, you have to avoid different things that expose you to mists or droplets of water.

That means taking baths instead of showers, for starters. If you’re filling up the sink, you should fill it up slowly, to avoid creating droplets of water that could transport bacteria. If you’re going to be boiling water for tea or coffee, you should start with cold water, rather than warm water, because the bacteria prefer water that’s warm, and cold water is less likely to generate mist. If you’ve got a humidifier, a clothes iron, or a steamer, you should probably avoid using them until the scare is past.

According to the Mayo Clinic, the disease is a lot more common in large buildings than it is in individual households. That’s generally because the plumbing and temperature regulation systems in those buildings are larger, more complicated, and thus more difficult to keep clean. When bacteria do take root, the complexity and size of the system makes them more difficult to reach and dislodge.

The bacteria are a bit curious in that they don’t usually travel on their own; instead, their modus operandi is to act as parasites of parasites. They typically hitch a ride with protozoans like amoebas, who provide them with the protection of a biofilm. Once they’ve armored themselves with that, the bacteria are particularly difficult to dislodge or destroy — the biofilms are resistant to most cleaning products and shield the bacteria and their hosts from the ravages of environmental changes, physical scrubbing, or other efforts to dislodge them.

Affected individuals typically start to show symptoms within two to ten days after exposure to the bacteria. Typical symptoms start with a headache, muscle pain, chills, and a fever. They’re quickly followed by coughing, chest pain, tightness in the chest, and difficulty breathing. Sometimes, the disease can also cause problems with the digestive system that are more in line with most of the pathogens that we write about here. That happens about half the time. Strangely enough, legionnaires can also cause neurological symptoms: they include loss of coordination, confusion, tiredness, and loss of appetite.

When left untreated, the disease can spin out into some very serious complications. You could go into respiratory failure, for example, with your lungs unable to provide the body with enough oxygen to stay alive. If the disease goes systemic, you could be stricken with septic shock, which can deprive your vital organs of blood and kill you. Legionnaires can even cause kidney failure, if you’re particularly sick or particularly unlucky. If you or a loved one is currently suffering from Legionnaires, consider speaking with a Legionnaires’ disease attorney to explore your legal options. Stay safe out there!

By: Sean McNulty, Contributing Writer (Non-Lawyer)