All fields are required

Posted in Outbreaks & Recalls,Salmonella on June 10, 2018

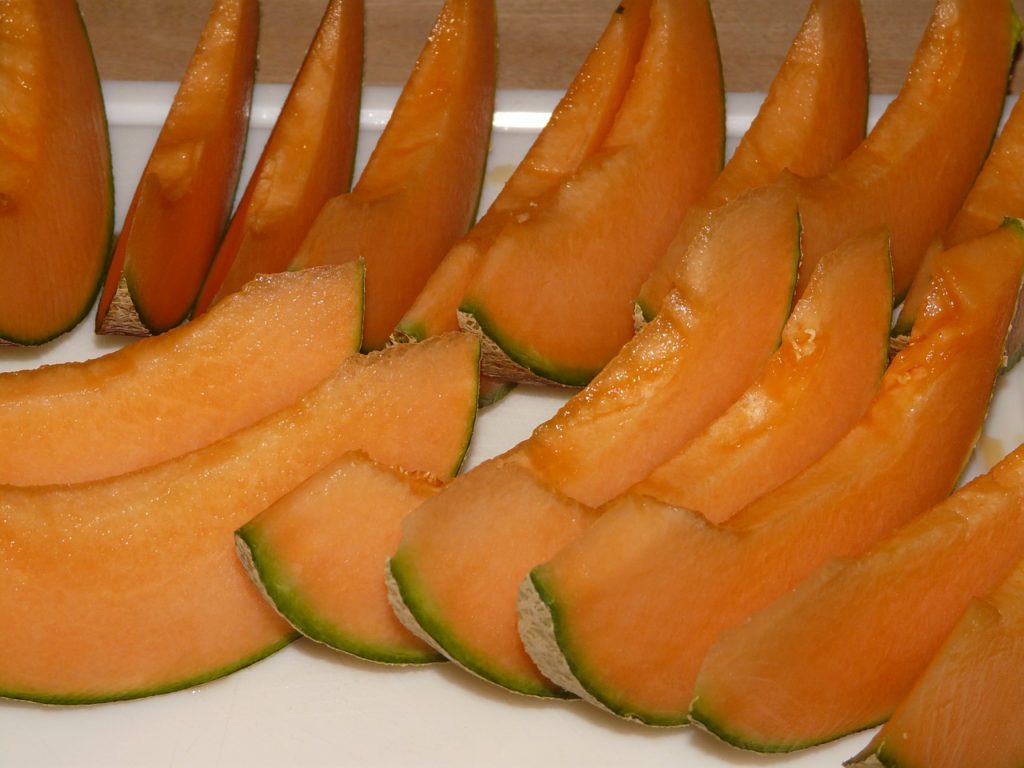

Health officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that dozens of people have been sickened in a Salmonella outbreak linked to pre-cut melon, Salmonella Pre-Cut Melon Outbreak.

The outbreak triggered a voluntary recall of pre-cut watermelon, honeydew melon, muskmelon, cantaloupe, and fresh-cut mixed fruit shipped between April 17th and June 8th. The products in question were sold at several grocery stores: Whole Foods, Jay C, Owens, Kroger, Trader Joes, Payless, Sprouts, Costco under the brand name Garden Highway, Walgreens as Delish, Walmart as Freshness Guaranteed.

Some of the product may have shipped before the recall was announced; because of this, it applies to both retailers and consumers. If you bought pre-cut melon in April, May or June from one of these retailers, you should return it or throw it away. We recommend taking a photo of any packaging you have and hanging onto your receipt, just in case.

Michigan is the hardest hit state, according to the CDC, with 32 reported cases. 11 cases were reported in Indiana, 10 in Missouri, 6 in Illinois, and 1 in Ohio. The pre-cut fruit linked to the outbreak was also sold in Georgia, Kentucky, and North Carolina, although no cases of Salmonella have been reported in those states as of the time of this writing.

The youngest person affected by the outbreak is an infant, according to the CDC. The oldest is 97 years old. The median age of victims is 67 years old. Two thirds of the victims for whom information is available have been hospitalized. No deaths have been reported so far.

Salmonella is one of the most common causes of food poisoning in the United States. According to the CDC, it’s responsible for more than a million illnesses, tens of thousands of hospitalizations, and hundreds of deaths each year. Food is the vector for the majority of Salmonella infections.

When someone comes down with a case of Salmonella, symptoms typically show up 12 to 72 hours after infection. The sickness typically lasts for four to seven days. Symptoms include diarrhea, fever, nausea, and abdominal cramps.

Healthy individuals don’t typically need to go to the hospital if they’ve fallen sick with Salmonella. In some cases, however, diarrhea can be so extreme that patients become dehydrated or experience damage to their digestive system. The Salmonella may spread from their intestines into the bloodstream, and from their bloodstream into other parts of the body.

This kind of severe infection is dangerous even for people who are otherwise healthy and can cause all sorts of very serious health problems. In some cases, it can even cause death. For the very young, the elderly, and the immunocompromised, severe infections with Salmonella are more common and more dangerous than they are for other populations.

Preliminary data collected by the CDC indicates that the pre-cut melon probably came from a distributor called Caito Foods LLC. Caito Foods is based in Indianapolis, Indiana, and has a large manufacturing facility there where the pre-cut melon was prepared and packaged into plastic. Investigators believe that the current outbreak of Salmonella can be traced back to that processing facility.

According to the Indianapolis Business Journal, Caito Foods was founded in 1965 by Philip J. Caito IV and Joseph A. Caito. The company makes some $600 million dollars a year, according to that article. In 2016, it was sold to SpartanNash in Grand Rapids, Michigan for $217.5 million.

The CDC was able to trace the Salmonella outbreak back to Caito Foods by asking people about the food that they ate and other “relevant exposures” that happened in the week before they fell ill. More than half of those interviewed reported that they had eaten pre-cut melon purchased from the grocery store. An additional seven victims reported eating melon but did not specify that it was pre-cut, according to a press release from the CDC.

After determining that the Salmonella likely came from melon, the CDC interviewed victims about where they had purchased their fruit. They discovered that many of the victims had bought from stores that stocked melons distributed by Caito foods.

Verbal interviews with the victims of an outbreak are just one piece of evidence. To determine that different cases of Salmonella are caused by a common strain of bacteria, the CDC uses a system called PulseNet. PulseNet draws from information gathered by a network of laboratories all over the country. Those labs are in communication with one another, and they coordinate to determine whether or not outbreaks in different cities and states can be traced back to bacteria who share a genetic fingerprint.

The CDC has a couple different techniques for determining genetic similarity between different pathogens. Their gold standard method for genotyping bacteria is called pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Fragments of bacterial DNA of bacteria are extracted. An electrical field is generated to sort those fragments by size, and they’re stained so that they shine under an UV light. This isn’t the most precise method of looking at DNA: it’s accurate enough to tell scientists whether bacteria are similar enough to be considered the same, but it’s not so accurate that it can provide a lot of specific information about the genes of those bacteria.

Another method for fingerprinting DNA is whole-genome sequencing. It’s slower and more resource intensive than pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, but it provides more detailed information about the genetic makeup of different pathogens; using whole genome sequencing, scientists can determine not just whether or not there’s a genetic relationship between bacteria, but whether those bacteria are resistant to different kinds of antibiotics, or whether they share a common genetic ancestor with one another.

The information gleaned from these analyses goes into the PulseNet database. It’s a gigantic, persistent catalogue of information about different kinds of bacteria maintained by the CDC. Investigators can thus draw links between pathogens separated by distance or time and determine whether or not they’re part of the same outbreak.

MakeFoodSafe will continue to follow the Salmonella in Pre-Cut Melons outbreak and related recalls and report details as they arise.

By: Sean McNulty, Contributing Writer (Non-Lawyer)